This January marks the 109th anniversary of Rocky Mountain National Park (RMNP). It was on January 26, 1915 that President Woodrow Wilson signed the bill that protected the 265,000 acres of pristine valleys and sublime peaks between the towns of Estes Park and Granby as the country’s tenth national park. However, it was largely due to the tireless efforts of advocates like Enos Mills that we get to enjoy RMNP as it is today.

Enos Mills may not be as renowned as other conservationists, like John Muir, but in Colorado he is known as the “Father of Rocky Mountain National Park.” For many years, Mills toured the country giving lectures and writing thousands of letters and articles lobbying for Congress to establish this national park. To me and others in my field of interpretation, though, he is also well-known as one of the country’s most influential nature guides. Learning more about Enos Mills’ life story will shed a light on both of these legacies.

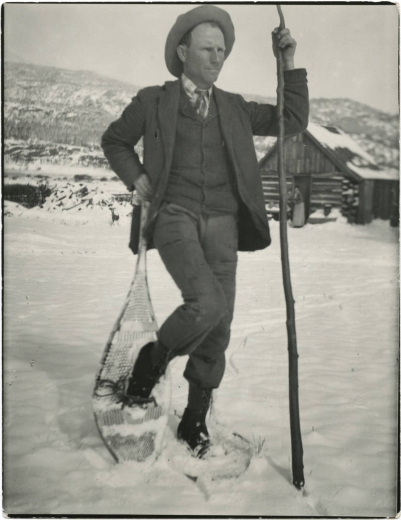

“Nature guiding, as we see it, is more inspirational than

informational.”-Enos Mills. Image courtesy of Denver Public Library

Enos Mills first came to Colorado as a teenager, by himself, and became enamored with the Longs Peak area when he drove cattle there one summer. He built his first cabin in the Longs Peak area at age fifteen, and spent his summers exploring the mountains. He made his first climb of Longs Peak that same year, and studied the ecology of the area using only library books to teach him. Mills traveled the country as he got older, writing nature adventure stories while he camped, and after a chance encounter with John Muir in 1889, he dedicated himself to conservationism. He purchased the lodge where he had once worked and renamed it the Longs Peak Inn, so that he could share his nature experiences with others. Longs Peak Inn became a popular tourist destination and a gathering spot for the intelligentsia.

In addition to being the father of RMNP, he is also considered to be the father of contemporary interpretation. Mills led about 250 trips up Longs Peak, and numerous other hikes, lectures, and campfire talks teaching people the natural history of the Rocky Mountains. In 1906, he established the Trail School, the first institution of its kind to train and certify naturalist guides in the United States. His teaching philosophy was further laid out in his 1920 book, “Adventures of a Nature Guide.”

You can visit a statue of Enos Mills and his dog Scotch in Estes Park

You can visit a statue of Enos Mills and his dog Scotch in Estes Park

Mills originally called the field of interpretation “nature guiding.” Training programs were soon established in many national parks based on Mills’ Trail School, and decades later, the National Park Service further distilled the principles of his book and renamed this burgeoning field interpretation. Many people aren’t familiar with this term, but have probably interacted with interpreters at places like national parks, state parks, historic monuments, and at Walking Mountains.

Rocky Mountain National Park today is the fourth-most visited national park in the country, and is so busy that it requires timed entry for drivers. As are wild places the world over, its fragile ecosystems are threatened by climate change and overuse. As I reflect on the history of this special place and the legacies of Enos Mills, I am so glad that we have interpreters to help share nature with people and remind them what’s at stake. On his own legacies, perhaps Mills put it best:

“The people of the United States have within the past generation created national parks, state parks, city parks, and made wildlife reservations, recognizing their higher values to people, for their uses in education, recreation and hopefulness. I wish that every park had a nature guide and that every wild place might early become a park.”

Hannah Rumble is the Community Programs Director at Walking Mountains. One of her favorite things about her job is training the Naturalists as Certified Interpretive Guides each year.